1950s Japanese cat's brain helps Canadian researchers solve mercury poisoning mystery

Sask. research project uses state-of-the-art technology to uncover secrets hidden in cat brain

By Alicia Bridges | CBC NewsIn the 1950s, a Japanese cat known as "717" helped solve the mystery of a mass poisoning in Minamata, Japan.

Now, almost 70 years later, a piece of brain tissue from the same cat has led a Canadian researcher and her co-authors to believe they have solved a toxicological mystery, as reported by CBC News.

Their breakthrough could eventually help save lives by treating and preventing some types of mercury poisoning.

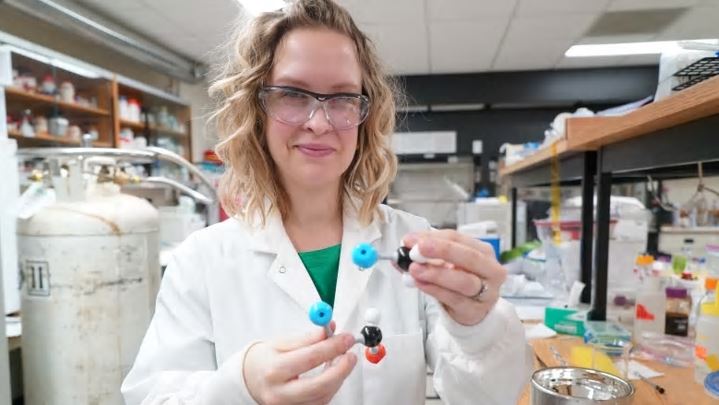

"It was really, really cool to see how science can answer questions from the past," said Ashley James (BSc'10, MSc'12), a PhD candidate in toxicology at the University of Saskatchewan.

Minamata and Grassy Narrows poisonings not the same

James compared the Minamata case with the mercury-poisoning at Grassy Narrows (Asubpeeschoseewagong), Ontario, the site of one of Canada's worst environmental disasters. Research suggests 90 per cent of the Grassy Narrows population still experiences symptoms.

Scientists originally thought that the poisoning in Minamata was caused by the same type of mercury — methyl-mercury — as in Grassy Narrows.

James's research, based on the decades-old feline brain tissue, suggests the two poisonings were caused by different materials.

Starting in the 1950s, people in the city of Minamata, Japan, started showing symptoms of nervous system damage, including loss of control of bodily movements, speech and swallowing, and sometimes death.

Cats in the area were showing similar symptoms. SNC Hospital director Hajime Hosokawa wondered if wastewater from the nearby Chisso Corporation's chemical plant — which was emptied into the local seafood source of Minamata Bay — could have been responsible.

In 1959 he started experimenting on the cats, including cat 717, to test the theory that the poisoning came from eating seafood in the bay. The cats eventually started showing symptoms of neurological illness and, in the same year, a report concluded that mercury poisoning was the suspected cause of the disease in humans.

About 2,265 people have since been certified by the Japanese government as having what is now called "Minamata disease" — more than 1,700 of them have died. Beliefs exist that the number of people affected could be higher.

There are different "species" of mercury — each made up of a different molecular compound.

Knowing which compound caused the poisoning could give scientists in the medical field more knowledge to develop treatments.

Until recently, scientists thought the poisoning in Japan was caused by the less-toxic form of "inorganic" mercury, which was released from the plant and then turned into "organic" methyl-mercury when it was dumped in the water.

Synchrotron finds answers in cat brain

James's research, completed with co-author Susan Nehzati and other researchers, concludes that the Japanese poisoning was caused by a completely different type of organic mercury that was discharged directly from the plant in a deadly chemical form.

Read more at https://www.cbc.ca/news/.