Doctors and elders unite to pursue equity in organ donations

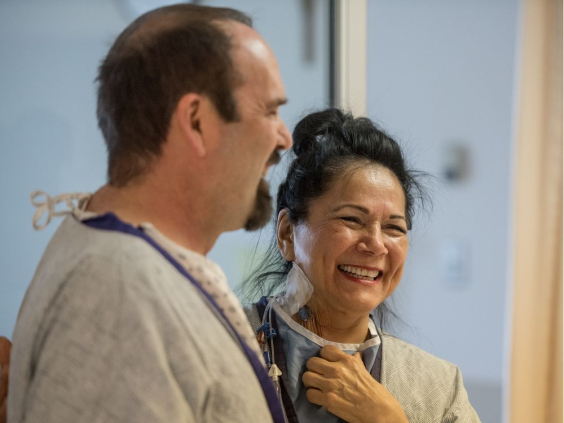

Monica Goulet (BA'96, MBA'07) received a kidney transplant in 2019. She is now part of a network aiming to help other First Nations and Métis people in the province receive the same gift of life.

By Zak Vescera | Saskatoon StarPhoenixOn a spring day in 2018, Monica Goulet felt worse than she ever had.

Goulet was living with kidney disease, a condition that left her feeling exhausted and made her body vulnerable to infection. On this day, she felt so awful that she called into the home of a neighbour, who helped her get an ambulance to the hospital.

The next year, Goulet received a kidney transplant from her nephew, Jimmy Searson (BEd'10, MNGD'18). She says the difference is night and day.

“I can’t even fathom how bad I felt,” he said.

Goulet is now part of a network aiming to help other First Nations and Métis people in the province receive the same gift of life.

Higher rates of kidney disease and other conditions driven by generations of health inequities mean Indigenous peoples in the province are significantly more likely to need a kidney transplant — but may also be less likely to get one.

While data is limited, a 2016 informal audit found Indigenous people made up 50 per cent of people in the province with kidney disease but only 15 per cent of those who receive a transplant.

“That’s kind of shocking, because the proportion of people in Saskatchewan who are Indigenous is only 16 per cent,” surgeon Dr. Michael Moser said.

Dr. Caroline Tait, a medical anthropologist at the University of Saskatchewan specializing in health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, met Moser by chance in a Denver airport and realized they were holding different pieces of the same puzzle.

The result is the Saskatchewan First Nations and Métis Organ Donation and Transplantation network, a group of elders, patients, students and professionals hoping to understand why the problem persists and how to solve it.

Tait says it’s a big change from how research of this kind usually happens in Indigenous communities. Instead of doctors and researchers coming to them, they’re proactively setting up talks between knowledge keepers, Elders and medical professionals.

“This is very different than what normally happens, when you have people inquiring about Indigenous peoples’ idea of different things,” Tait said. “In this context, we wanted to flip that on its head.”

The project has received nearly $50,000 from the Royal University Hospital Foundation in May 2019 and $180,000 from the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation and Saskatchewan Centre for Patient Oriented Research to explore organ donation and transplantation issues for First Nations and Métis people.

Moser said a shortage of organ donors is in many ways a provincewide concern.

While Saskatoon was the site of the second solid organ transplant in Canadian history in 1963, the province today has one of the lowest living and deceased donor rates in the country, according to Canadian Blood Services, and no presumed consent for organ donations.

The province has announced an organ and tissue donor registry will be available sometime later this year.

Ernest Sauve, a knowledge keeper and Elder from James Smith Cree Nation, said the challenges of finding donors are even more pronounced in First Nations and Métis communities.

“There is some general sense among our traditional knowledge people that the body needs to be whole to enter into the spirit world,” Sauve said. “So that would hamper removal of organs upon end of life.”

Sauve said the network has already helped facilitate exchanges between surgeons and Elders to help find common ground. It’s also highlighting the need for more access to resources about organ donation in Indigenous languages like Cree, particularly for older generations.

“That is one of the challenges that we have now, is to see if we can change the particular position of our particular belief system,” Sauve said.

Tait and Sauve say COVID-19 only furthers the need for the network, given the unequal access to medical services in the province’s north.

Goulet said her biggest hope is that her experience, and the network’s efforts, will help provincial authorities recognize and fight those disparities.

“We need to reach out to the people that need the most help,” she said.

Article originally published on https://thestarphoenix.com.